This Autumn’s issue of the Recipe Project, guest-edited by Alexandra Macdonald, explores the relationship between images and recipes as they proliferate in our contemporary digital world, and as they informed peoples’ perception of the recipe and its function in the distant past. Below, we share this month’s Introduction, written by Alexandra, and invite you to visit the Recipes Project every Thursday from now until November 7 to read new posts dropping every week!

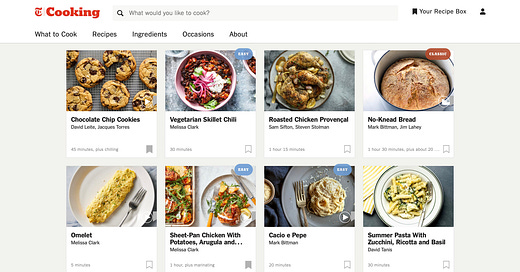

Sometimes seeing is better than telling. With a renewed interest in DIY, recipes are everywhere. Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok are full of recipes and many, if not all, of them use captivating visuals to educate and inspire viewers. New York Times Cooking (@nytcooking), for example, has 4.1 million followers and a quick scroll though their page is a veritable feast of visual storytelling where gooey cheese, crisp apples, and bubbling pots of soups from around the globe introduce viewers to both step-by-step instructions and personal and cultural stories.

While visual-centric social media platforms are a modern phenomenon, as the posts in this issue illustrate, for hundreds of years and across a number of cultures, images have been used to craft stories around recipes. Whether the medium is digital, print, or manuscript, turning the physical act of making into a visual narrative requires interpretation, and images rarely serve a single goal; they are packed with assumptions, omissions, and expectations. The images that accompany recipes, or images that themselves function as instructions, can tell us as much about the development of a national or immigrant identity, the politics of mass-produced goods, racial and gender biases, or health practices as they do about the intricacies of any given recipe.

Because images have been so widely used in the storytelling that often accompanies recipes, the posts in this issue cover a broad range of regions, time periods, and cultures. However, several themes emerged that unite the issue’s essays.

First, we see images being used alongside recipes in advertising. And there is perhaps an equally robust tradition of advertisers using those images to do far more than communicate information about the recipe at hand. In her examination of propaganda posters from second-world war era Ceylon, Lara Wijesuriya shows how the visual recipes used to teach women how to cook wheat instead of more traditional rice-based dishes not only communicate information about the recipes themselves but provide insights into colonial notions of gendered labor and ‘home science.’ Jennifer McGillan’s study of mid-twentieth century promotional materials produced by Heinz Ketchup reminds us that imagery that was intended to educate can also feed into and reinforce stereotypical representations of ‘foreign’ people and cultures. Working in a similar vein, Simone Gillespie’s examination of advertisements run by the Duke Power Company in the twentieth century show how the company used their mascot Reddy Kilowatt and his “Recipe for a Healthy…Happy Wife” to craft a narrative in which women were told the key to happiness was to be hospitable servants to their family’s needs. Playing with the idea of both “time-honored” definitions of advertising and recipes, Xaq Frohlich’s examination of the FDA’s introduction of the Mellorine Standard in 1973 explores what happens when a ‘recipe’ is used to regulate mass-produced foods.

Images have also been used to communicate information across cultures. In her study of early American cookbooks, Jennifer Wells reminds us of the complicated relationship between ‘American’ and ‘British’ or ‘European’ cookery, suggesting that early American women used cookbooks to develop their understanding and performance of a national identity by both ridiculing and emulating British practices. Writing on the transfer of knowledge across the English Channel, Lauren Owens explores how French cooks adapted plum pudding, a quintessentially English dish, to suit their distinct geographic and culinary contexts. Haritha Govind’s examination of the video game Venba reminds us of the power of immersive visual storytelling. Introducing players to South Indian cooking through the well-loved pages of Venba’s mother’s cookbook, the game’s imagery and pacing encourages players to uncover the layers of cultural and culinary meaning hidden in the smudged recipe book.

Materials and memories are at the heart of a number of recipes, and visual storytelling has also been used to convey information about the materiality of recipes and the memories they can elicit. In her study of imagery from a sixteenth century Chinese book on the art of living, Cheng He shows how illustrations could function not only as visual descriptions but as aesthetic expressions of complex ideas. In portraying a series of inkstones, the author not only communicated important information about the materiality of stones used to grind ink, but he sought to communicate the importance of nourishing one’s soul as well as one’s body. Exploring the sticky problem of sap, Tedi Pascaella reminds us of the importance of materials and offers an introduction into the complex history of the healing properties of mastic sap in a global context. Sonakshi Srivastava’s photo-essay plays with both the structure of a recipe and the role of images to explore the relationship between food, crafting, and the senses to show how the art of making ghuiyan ke patte ki pakodi (fritters made from yam leaves) conjures images of her mother’s hands moving through the crafts of daily life.

Taken together, the essays in this issue argue that images played, and continue to play, a crucial role in learning not only new culinary skills but in understanding the personal and cultural worlds recipes inhabit and can create. For us, the fascinating and multifaceted picture that emerges from these essays enriches and extends current studies of recipes, and we hope that they inspire others to explore the rich and complex world of images!